Andalusian Muslim women’s gender expectations in relation to social class, time, and comparable laws were determined by women’s social status in Medieval Iberia under Muslim rule from 10th century to 13th century. By reflecting on these gender expectations that were considered virtuous by looking at the way women were behaving under different circumstances from different narrative in primary sources and secondary sources within the topic, in order to gain holistic understanding of the social and political context, one other aspect of this research is to see if these concept had changed over time from the golden age of Umayyad Caliphate until the final Taifa period where Muslim dominance in Iberia waned. In order to compare and contrast these works, elements we must look at from the two primary sources are: the perspective and the narrative of the story; what the story is about; social status of the characters;the reflection of gender expectation through the literature.

The passage The Ring of the Dove written by Ibn Hazm was written approximately from the beginning of 10th century in Cordoba.(Constable & Zurro, 2012) It is a famous piece of literature that was compared and contrasted by many authors in medieval writing until today. The author Ibn Hazm fell in love with a slave girl in his household when he was a teenager, and the text itself demonstrates his feelings for her changed overtime during the political influence that was brought to his family during the period of Umayyad civil war. Ibn Hazm’s father worked as a Vizier for Almansor, but his family was forced into hiding after Almanzor died and Hisham II took the throne for the second time, so basically their family is on the opposite side of the power. Ibn Hazm went back to his hometown Cordoba after a few years, he met the slave girl again at a relative’s funeral, however, he realized to him, her beauty faded away when she was not protected under the household.(Dangler, 2015)

In this case, Ibn Hazm was fond of the girl’s avoidance, delicacy, chastity and purity; what was attractive to him was the way she kept herself distant. Ibn Hazm tried to approach her during a family gathering, but he did not try to break their distance, but in a position of spectator of her change after they had left Cordoba. However, she does not appear charming to him anymore after the family moved away without her, so she has to find a living on her own. Meanwhile, Ibn Hazm criticized that she was losing her beauty because of lack of maintenance overtime.

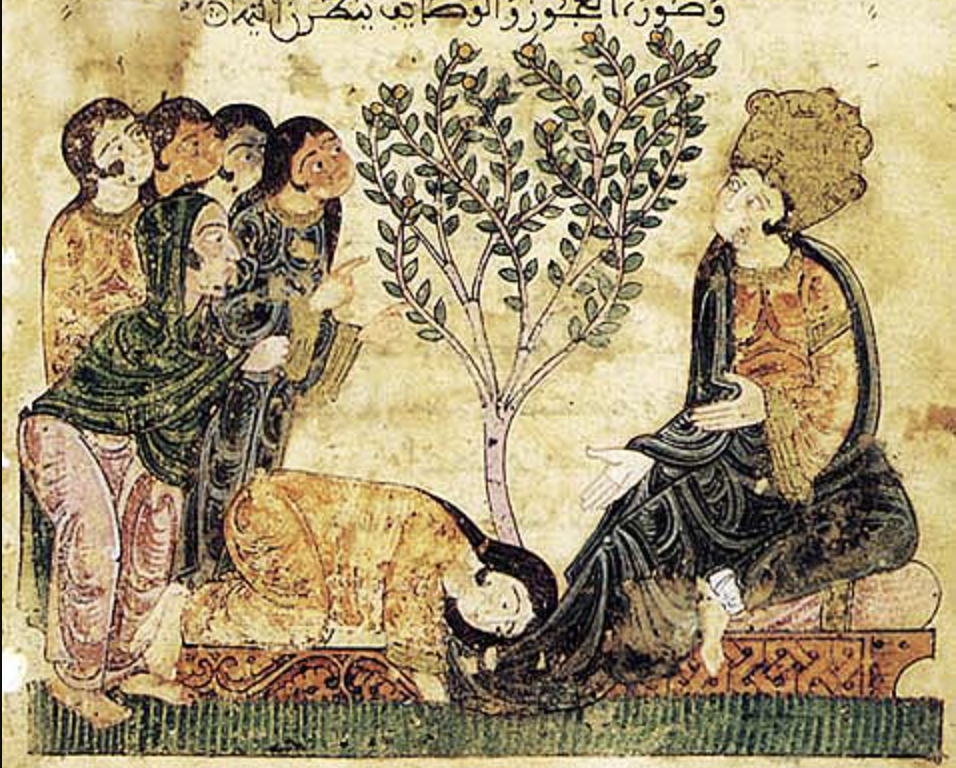

The text “Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad” translated by Barbara Cynthia Robinson from Arabic is a story that happened in around 13th century Al-Andalus, it comes from a female narrative of a ajuz, which could be understood as matchmaker, someone that helps setting lovers up for meetings.(Cynthia Robinson, 2007) This love story happened between the Merchant’s son from Syria, Bayad, and the slave girl of hajib’s daughter Sayyida named Riyad. The matchmaker set Bayad and Riyad up at a gathering in Sayyida’s garden, where everyone sang songs and poems. While Bayad admitted his crush on Riyad in an obscure way, by complimenting on her beauty, which everyone was impressed about, Sayyida was furious at Riyad while she realized it and responded to him in a much more blunt and straightforward poem because she was not maintaining the characteristics that she was supposed to, it was a serious problem for Sayyida because she was going to exile her from the household sell her on the market. This manuscript reflects the gender expectations in 13th century Al-Andalus and provides some insight into the virtues that women should have in relation to their social class.

For instance, Riyad, as a slave girl has the lowest social status, Bayad and Sayyida have more power to make decisions in the society. Thus, the one obvious outcome of Riyad expressing love directly to Bayad was considered rude and out of character, and was heavily criticized in the story. In comparison, Bayad was able to openly sing the song to Riyad without causing any troubles. According to Bayad, while he was describing Riyad, he liked her and praised her characteristics for being shy, beautiful and silent.(Cynthia Robinson, 2007, p. 33)Moreover, when the old lady was trying to comfort Sayyida for Riyad’s action, she stated that “for we are all women and we have no reason and so we don’t know how to guide ourselves— how can we guide ourselves, then? There’s no blame in what Riyad did…” she used ‘ourselves’ in the choice of word specifically, this could indicate that the idea of the dependant as the stereotype for muslim women in 13th century Iberia exists regardless of their social status.(Cynthia Robinson, 2007, p. 36) Though Sayyida’s words while she was angry suggested that she had the power to decide for her slave’s life since Sayyida’s father wanted Riyad as his mistress, which shows upper class males are able to openly express their love affection but women have much less likely chance to do so, near the end of the manuscript, it was revealed that the person who kept the lovers from seeing each other was the hajib, meaning that the right to choose their loved ones is largely based on one’s social status. Meanwhile, more than one spot in the story stated that women are supposed to be silent, beautiful, chaste and dependent.

There are some similarities of what both women were facing in the story The Ring of the Dove and Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad. Both love stories began with love at first sight from the male perspective without having the process of further knowing each other, and kept a moderate distance between each other because of the need to examine if the woman was being unrevealed and chaste. Both stories highlight men’s affection and social acceptance for women was largely based on females’ restrained, meekness and purity. It was shown in The Ring of the Dove where Ibn Hazm finally met her at the family gathering when she was trying to stay away, it also shows when he saw her again years after saying all her beauty and attractive traits faded away, which including her fragileness and shyness. It is similar in Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad after Riyad expressed her feelings to Bayad in the poet singing activity, everyone in the garden was in shock that she did such an action. Riyad was punished by her master, Sayyida for this inconsiderate act, which proved that it is not socially acceptable for women to do so directly. While the identity of both female characters were slaves in these stories, the male character in both stories had higher social status than women, Ibn Hazm was a poet and came from a well-educated elite family, Bayad was a Syrian merchant’s son. While the male characters maintain their higher social status, there is no sign of forcing the girl to be together in both stories, except for the hajib, Sayyida’s father, who tried to ask to take Riyad through her daughter. It is slightly confusing and contradictory that through Sayyida’s words it seems like slaves in these households can just be traded and sold in the market. However, unlike the hajib, both Ibn Hazm and Bayad showed their respect when they were going to approach the women they love, although Riyad and the slave girl in The Ring of the Dove were both from lower social status.

Although there are some common themes in women’s life related to love affairs in both of the stories, there are also many elements that can influence the reality of their life. First, the perspective of these two texts are distinctively different, thus it would be subjective when the individual is judging or recalling certain events, which should be taken in consideration while investigating the story. The narrator from The Ring of the Dove, Ibn Hazm, his philosophical and political experience the changed for himself, also lead to his father’s pass away, according to the textbook, his feelings for the slave girl is also an implication for his hometown changed and declined throughout the first fitna, so the metaphor was also used on his past experience with the one he loved.The mindset when Ibn Hazm was creating in this book also constitutes his cherish to the past. Whereas Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad has a completely different narrative, this story also comes from the ajuz that experienced it, however, the perspective shifts around the main characters. However, the effect of the ajuz is actually a treasure and cherishes the appearance of true love.(V. Besprechungen, 2009, p. 364) Furthermore, sometimes women’s ability and events are marginalized in historical literature and documents, making it challenging to interpret when connected to other background information. (Shamsie, 2016) In these two texts, both muslim women had very different endings, in The Ring of the Dove,the slave girl did not overstep the boundary, facing Ibn Hazm’s love and admire, she still held her behaviour of moderation and self-control, even if toward the end when Ibn Hazm changed his emotions, she did not change. In Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad, Riyad did not choose to follow the widespread and accepted idea of holding in her own emotion, but to follow her heart to express her love to Bayad. At the end, Bayad and Riyad reunited successfully, but the voices against them from the society emerged in the literature during their effort towards reunion.

In relation to Islamic law, the reason women or people in general show less affection is also because their spirit should be submissive to God, so to distribute this energy to the person that they love is considered wrong in Islamic definition.Because one’s soul should not be dominated by a human being.(Benaim de Lasry, 1981, p. 136) This point can be supported with quotes from the poems in Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad, “Love holds absolute power over my soul… It’s terrible power breaks me to pieces through desire, causing me pain and tears.” “And melted my body from the pains of love–I was left without my soul.” When they are describing love in their literature, it comes out as comparatively negative phrases although they are passionate about each other. The indirect expression continued in the 13th century, where ajuz acted like “go-between” in the lover and the beloved to balance it out.(V. Besprechungen, 2009) Furthermore, only men in islamic iberia were allowed to permit marriages, very few women at the time had the right to decide on their own marriage.(Coope, 2017b, p. 89) According to Coope, in Earlier Al-Andalus, around 9-10 centuries, because women’s action were not taken seriously in the society, the fact that the patriarchal society reinforced the idea that in relationships and marriages that women should be submissive and distant, which continues to have impact on how islamic society went about defining intersex relationships, and expected women to be that way.(Coope, 2017a)

In conclusion, by coming to understand these gendered relationships, with the focus on female gender expectations in Islamic Al-Andalus, interpreting these relationships to other social elements such as social and legal systems the nature of patriarchal society is revealed. The two texts, regardless of social status, it is not socially acceptable for Islamic women in Al-Andalus to express their love directly. Though better social status brings a variety of possibilities to their own choices and sometimes even other people from lower social status. This is a symptom of larger developments in the Islamic world but the unique scene painted by these authors in Al-Andalus provides us with a means with which to view these trends through.

Reference

Recent Comments