Crusading Impact on Christian Iberia

Luke Frolick

History 365 Medieval Spain

June 27, 2021

Throughout European history, Iberia had the unique distinction of sustained religious tolerance in comparison to its neighboring countries. While conflict still existed, the majority of it stemmed over rulership, with most rulers allowing some sort of religious freedom. When the Crusades began, the Roman Catholic Church declared Christian supremacy which was enforced with war and violence. The goal was to take Jerusalem back from the Muslims and eradicate them. While a fury rose up over Europe, it didn’t take hold in Iberia immediately. Through persistence of the Church, we’ll look at how Christian extremism was able to erode relative tolerance by focusing on this one side of the conflict.

The Umayyad Dynasty began rule in Iberia in 756, with its capital in Cordoba. It encompassed all Iberia but a few small Christian kingdoms in the North, and part of Northern Africa. This dynasty prospered and in the tenth century, it was one of the wealthiest nations at the time and a major cultural center. After the collapse of the Cordoban caliphate in 1031, the unity under a single ruler collapsed with it. Smaller taifa kingdoms from across Iberia competed with each other for supremacy. As some kingdoms had wealth, but not enough people, they hired outside protection through mercenaries. The gold offered was enticing to the Christian lands in the North, and so Christian kingdoms entered into alliances with the taifa kingdoms. This caused infighting and conflict between mercenaries whom had no religious affiliation, were Christians, Muslims or Christians alongside Muslims. Religion played little to no factor in any of the fighting.

An example of the most famous mercenary was the Castilian nobleman Rodrigo Diaz, commonly referred to as El Cid, who lived from 1045-99. Through his military career, he served under the Christian Kings Fernando I of Leon-Castile, his son Alfonso VI, then followed by fighting for the Arab Muslim emir of Zargoza.[1] After this service, he set up his own army, made up of Christians and Muslims. From 1089 he fought independently until he took the city of Valencia, where he set himself up as taifa ruler.

Chronicle of the Cid, a medieval document covering the life of Rodrigo Diaz, comments on taking the city of Valencia. Though a predominantly Christian city, the Cid ensured both groups would be able to live alongside each other. “He commanded and requested the Christians that they should show great honor to the Moors, and respect them, and greet them when they met: and the Moors thanked Cid greatly for the honor which the Christians did them.”[2] Although the Cid clearly had no religious motive in his exploits, he was later held up as a Christian warrior, highlighting specific battles. This was not the first or only time events would be appropriated for specific religious goals.

The Chanson de Roland (Song of Roland) is an early example of Christian propaganda to fuel the Crusades and Reconquista in Spain. The original eighth century ballad, passed down orally, recounted the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, where Charlemagne’s army is ambushed by Basque rebels on their return to France from Spain. When eventually written down in the eleventh century, details were drastically changed or removed by the author to create a distinctly religious conflict in the narrative. Left out were details that Charlemagne allied himself with the Muslim ruler of Saragossa on his expedition into Northern Spain. The Christianized Basques were turned into demonic, pagan, Islamic barbarians. The entire perspective of Christians fighting Christians is removed. The battle changed into a large scale martyrdom of Christian Knights. Roland was one such knight and portrayed the hero, fighting for Charlemagne. His battle cry, “Pagans are wrong, Christians are right” creates a black and white narrative, with clear distinctions as who is right and wrong.[3] The song concludes with Roland receiving the highest divine reward upon death, “And God sent to him his cherubim, and St. Michael of the seas, and with them went St. Gabriel, and they carried the soul of the count into paradise.”[4]

These stories of heroism were also backed by papal support for religious conflict. In rallying support for the Holy Crusade to take Jerusalem, Pope Leo IV, followed by Pope John II made multiple declarations from 847-848, called “indulgences,” as rewards for killing Muslims. These indulgences would act as a penance, absolve one of nearly all sins and guaranteeing them a heavenly resurrection, among other blessings.[5] Initially only applying to the Franks, in the areas that would become France, these indulgences proved popular among the people. They would later extend to pilgrims to encourage taking Jerusalem and in 1089 and 1091, Pope Urban II included the same indulgences to campaigns in Spain. The First Crusade to Jerusalem would prove more appealing, even to Spanish Christians,[6] however, the seeds were planted by that declaration to increase religious fervor in the decades to come.

As the twelfth century continued, the Christian influences previously mentioned began to have a greater hold on Northern Europe. The Chronica regia Coloniensis (Royal Chronicle of Cologne), a historical record written in the second half of the twelfth century, contains a series of letters attributed to a Bishop of the Roman Catholic diocese of Porto. These letters set a precedent for future perceptions of Iberian conflicts from the late eleventh through the early twelfth century, the time surrounding the First Crusade. The conflicts are described as an extension of the Eastern Crusades, claiming suffrage of the Iberian Christians at the hands of the Muslims. As the Second Crusade was beginning to take shape in the mid-twelfth century, the Christian participants from Northern Europe felt obligated to support the war effort, rallying under religion.[7]

In 1147, Pope Eugenius III declared a Second Crusade. The call was made to take back Edessa, a county set up during the First Crusade, which was captured in 1144. In addition, there would be an effort to take Damascus.[8] Many answered the call, as penance, devotion to God and for glory, ideals the Church had been propagating for well over a century.

During this time, Alfonso VII of Castile had been involved in regional conflicts to assert his claim as King over Castile and Leon. Despite being a conflict over rulership, Alfonso took advantage of papal support for the eradication of the Muslims and altered his motivations to that of being a holy war. This came along with the benefits of indulgences and would garner him more support.[9] It would be at the siege of Lisbon that Alfonso would be able to take advantage of the traveling Crusaders from the North.

The most efficient route to the Holy Land was by ship. Many of the Crusaders from Northern Europe sailed along the East Coast of France, around the entire Iberian Peninsula, then West across Southern Europe towards Jerusalem. Heeding the call, the initial fleet that launched in 1147 was fairly substantial. As they approached Lisbon, on the Western coast of Portugal, they saw that it was besieged by Alfonso VII. As a predominantly Muslim city, Alfonso was able to convince this force to aid in taking Lisbon. A document from the time describes the city as “the basest element from every part of the world had gathered there, like the bilge water of a ship, a breeding ground for every kind of lust and impurity…”[10] which fueled the Crusaders righteous indignation. Despite the city surrendering relatively quickly, there were many problems that arose, both during and after the siege.

Among Alfonso’s Portuguese contingents, many of the troops that arrived were from different countries, but also from splintered groups inside those countries. “Norman, Anglo-Norman, Frankish, Gascons, Flemish, Frisian and Rheiners”[11] made up the siege forces, with many of them in conflict back in their homeland. Being forced into relatively close quarters created disputes which could have worsened had the siege lasted longer. After the siege ended and the terms for surrender were made and accepted, due to tensions from culture, religion or both, they were violently broken. “The men of Cologne and the Flemings … did not observe their oaths or their religious guarantees. They ran hither and yon. They plundered. They broke down doors. They rummaged through the interior of every house. They drove the citizens away and harassed them improperly and unjustly. They destroyed clothes and utensils. They treated virgins shamefully. They acted as if right and wrong were the same. They secretly took away everything which should have been common property. They even cut the throat of the elderly Bishop of the city, slaying him against all right and justice…”[12] The same document then mentions how the Normans and the English “for whom faith and religion were of the greatest importance” stayed true to their oaths and “obligations of faith.”[13] This account tries to give reason and blame to the chaos taking place, as it would have been too rampant and extensive to exclude.

The success in taking Lisbon further emboldened Crusaders to attack cities along the al-Andalusian coast. While the Almoravids of al-Andalus were defending themselves from the Almohads, an extreme Islamic group from Northern Africa, Crusaders were left with little opposition. By 1149, along with Lisbon, the tifa of Tortosa and the port city of Almeria were taken.[14]

The failure of the Second Crusade was characterized by not being able to take Damascus. Like the different groups fighting in the siege of Lisbon, lack of cohesion, and very likely conflict between the armies of France, Germany and Jerusalem played a part in that failure. The kings of each respective country blamed each other for their defeat.[16] Turning attention away from this failure, victories in Iberia were emphasized to prove Crusaders still had divine support. The concept of Reconquista, taking back previously Christian lands from the Muslims, became more propagated. It would increasingly be used in reworking past conflicts and as a basis to garner support for the Catholic Church and Christian rulers.

Throughout the next half century, rulership was contested in Iberia in many conflicts, mainly due to politics, not religion. Through the Third and Fourth Crusade, Spanish Christians were comparatively involved very little, being more concerned about their living conditions at home. Outside forces did pose a threat along the coasts of Iberia as indulgences were still granted to fighting the Muslims in Spain. Northern Europe still circled the coasts of Iberia to get to Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Crusaders were eager to raid and plunder on their journey, with little regard as to whether they were sacking Christian, Muslim or mixed communities, taking advantage of the civil strife in the area.

In 1213, Pope Innocent III in preparation for a Fifth Crusade, revoked the offer of indulgences in Spain, except for the Spaniards themselves. This was to focus on the war in taking back Jerusalem, rather than Spanish exploits.[17]

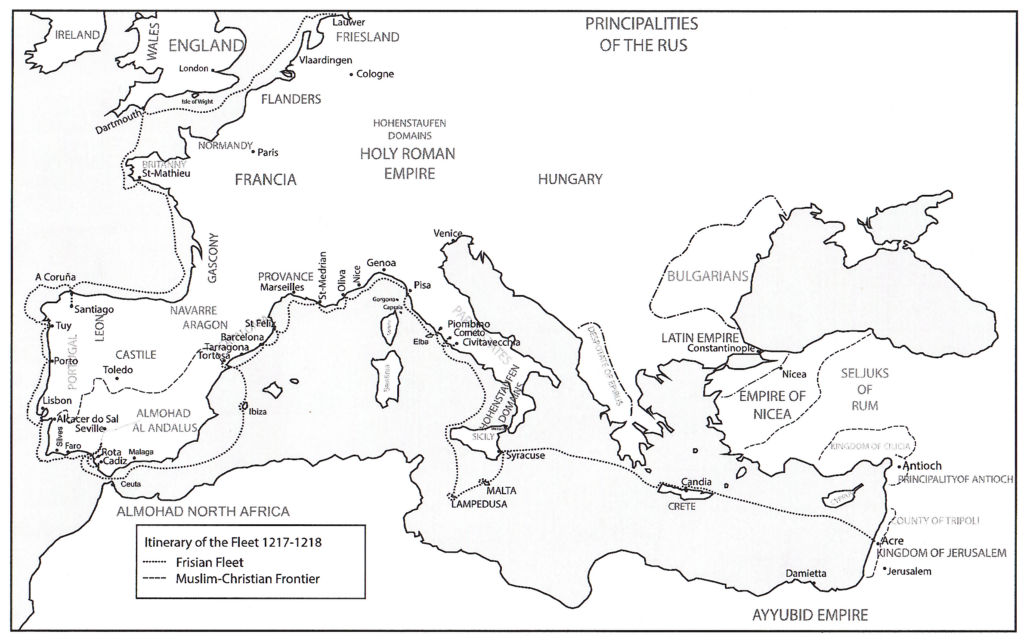

With the Fifth Crusade beginning in 1217, despite the cancellation of the indulgences, Crusaders traveling the Iberian coast continued their raiding and aggression on their journey to the Holy Land. Over a century of propaganda, holy Christian wars and demonizing the Islamic people had rooted itself in the minds and culture of those participating in this Crusade. An eyewitness account, from the Dutch-Latin document, De Itinere Frisonum describes the journey of a Frisian fleet from its departure on May 31, 1217 to April 26, 1218 when it lands in Acre. The document carries the theme of Christian redemption along with references to previous Crusader exploits and victories in Iberia, such as the conquest of Lisbon among a few others. This fleet was no different and continued to sack Andalusi cities. The reason for this, was in imitation of previous Crusaders. Attacking and raiding these cities was just as much a part of their Crusade as fighting in the Holy Land. While this document wasn’t heavily circulated at the time, by the end of the sixteenth century, this story was well known in Friesland.[18]

As the map shows, the journey of the Frisian fleet holds very closely to the routes described in the earlier crusades, even landing in some of the cities and ports of past exploits. This journey was a pilgrimage itself, in following their ancestors or heroes. Until the crusades ended, the act of pilgrimage and raiding continued, whether they had papal support or not, because it had become a tradition.

These external influences and attitudes were the beginning steps in creating specifically religious conflict throughout Iberia. Religious minorities would find it increasingly difficult to live and cities and territories would be increasingly pressured to be either Christian or Muslim.

As the long rule of the Caliphate came to an end, the power vacuum left behind created smaller kingdoms which were in a state of constant struggle for domination with each other. With the Roman Catholic Church trying to increase its influence over Europe, Iberia continued to be the exception. Religious tolerance was more prominent than in other countries. While there was still conflict, it was mostly about land and rulership as opposed to religion. Christians and Muslims fought alongside and against each other, and amongst themselves. Through creating a narrative of Christian verses pagan, while rewriting historical events, and prejudiced propaganda, the Church slowly eroded Christian Muslim sympathies. Through the onset of the Crusades, Northern Europe slowly imposed Crusader ideology throughout Iberia. With the invention of Reconquista, indulgences and violent tradition, the true complexity of their history slowly faded into simplistic battles of religion.

Bibliography:

Allen, S. J., and Emilie Amt. The Crusades: a Reader. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Allen, S. J., Emilie Amt, and I. Butler. “The Song of Roland.” Essay. In The Crusades: a Reader, 22–24. North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Allen, S. J., Emilie Amt, and R. Southey. “Chronicle of the Cid.” Essay. In The Crusades: a Reader, 288–91. North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Allen, S. J., Emilie Amt, C. W. David, and J. A. Brundage. “The Conquest of Lisbon.” Essay. In The Crusades: A Reader, 292–96. North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Allen, S. J., Emilie Amt, O. J. Thatcher, and E. H. McNeal. “Early Indulgences.” Essay. In The Crusades: A Reader, 17. North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Ayala, Carlos De, Francisco García Fitz, Santiago J. Palacios, and Lucas Villegas-Artistizabal. “Las Guerras Peninuslares Contra Al-Andalus: Una Vision Desde Las Fuentes Narrativas Unltramontanas (c. 1064-c. 1217).” Essay. In Memoria y Fuentes De La Guerra Santa Peninsular (Siglos X-XV), 103–29. Madrid: Trea, 2021.

O’Grady, Selina. In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance. London: Pegasus Books, 2020.

Rosenthal, Joel T., Paul E. Szarmach, and Lucas Villegas-Aristizabal. “A Frisian Perspective on Crusading in Iberia as Part of the Sea Journey to the Holy Land, 1217-1218.” Essay. In Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History 15:67–149. 3rd Edition. Tempe: ACMRS Press, 2021.

Tyerman, Christopher. The World of the Crusades. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

[1] Christopher Tyerman, The World of the Crusades (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 288.

[2] S. J. Allen, Emilie Amt, and R. Southey, “Chronicle of the Cid,” in The Crusades: a Reader (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014), pp. 288-291, 289.

[3] Selina O’Grady, In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance (London: Pegasus Books, 2020), 117,118.

[4] S. J. Allen and Emilie Amt, “The Song of Roland,” in The Crusades: a Reader (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014), pp. 22-24, 24.

[5] S. J. Allen and Emilie Amt, “Early Indulgences,” in The Crusades: A Reader (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014), p. 17.

[6] Christopher Tyerman, The World of the Crusades (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 291.

[7] Carlos De Ayala et al., “Las Guerras Peninuslares Contra Al-Andalus: Una Vision Desde Las Fuentes Narrativas Unltramontanas (c. 1064-c. 1217),” in Memoria y Fuentes De La Guerra Santa Peninsular (Siglos X-XV) (Madrid: Trea, 2021), pp. 103-129, 117.

[8] Selina O’Grady, In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance (London: Pegasus Books, 2020), 136.

[9] Christopher Tyerman, The World of the Crusades (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 173.

[10] S. J. Allen and Emilie Amt, “The Conquest of Lisbon,” in The Crusades: A Reader (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014), pp. 292-296, 293.

[11] Carlos De Ayala et al., “Las Guerras Peninuslares Contra Al-Andalus: Una Vision Desde Las Fuentes Narrativas Unltramontanas (c. 1064-c. 1217),” in Memoria y Fuentes De La Guerra Santa Peninsular (Siglos X-XV) (Madrid: Trea, 2021), pp. 103-129, 116.

[12] S. J. Allen and Emilie Amt, “The Conquest of Lisbon,” in The Crusades: A Reader (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014), pp. 292-296, 295.

[13] S. J. Allen and Emilie Amt, “The Conquest of Lisbon,” in The Crusades: A Reader (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014), pp. 292-296, 296.

[14] Selina O’Grady, In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance (London: Pegasus Books, 2020), 137.

[15] Christopher Tyerman, The World of the Crusades (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 295.

[16] Selina O’Grady, In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance (London: Pegasus Books, 2020), 137.

[17] Selina O’Grady, In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance (London: Pegasus Books, 2020), 296,297.

[18] Lucas Villegas-Aristizabal, “A Frisian Perspective on Crusading in Iberia as Part of the Sea Journey to the Holy Land, 1217-1218,” in Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History, vol. 15 (Tempe: ACMRS Press, 2021), pp. 67-149, 76-80.

[19] Lucas Villegas-Aristizabal, “A Frisian Perspective on Crusading in Iberia as Part of the Sea Journey to the Holy Land, 1217-1218,” in Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History, vol. 15 (Tempe: ACMRS Press, 2021), pp. 67-149, 109.

Recent Comments