The Virgin Mary holds a special place within Christianity, which can be seen throughout religious texts and artworks throughout the medieval period, particularly in Spain. Worship of the Virgin Mary has been an important aspect of Christianity since the fifth century, during which time the Council of Ephesus sanctioned the cult of the Virgin as Mother of God. For my project, I have chosen to focus on the significance of the Virgin Mary to Christian women in medieval Spain, through my analysis of Leonor López de Córdoba’s autobiography, Memorias. This source, which comes from the early fifteenth-century, is “often considered the first autobiography written in Spanish, and [has] also attracted the interests of critics as one of the earliest Peninsular texts to be authored by a woman. While the text is an autobiography and documents the events of López de Córdoba’s life, it is also a religious document, as she dedicates the work to God and the Virgin Mary, stating in her introduction, “And so that whoever hears this knows the story of the deeds and miracles the Virgin St. Mary showed me, and as it is my intention that these deeds and miracles be remembered, I ordered this to be written.” Here, she clearly states that her purpose for writing is to record the miracles she has experienced because of her faith in God, and encourage others to share that faith, so that they may experience the same miracles and be “consoled” by God as she has.

While López de Córdoba does praise God himself within the text, she places a special emphasis on the Virgin Mary, which was not uncommon during the late medieval period, as “the twelfth and thirteenth centuries saw an extraordinary growth in the cult of the Virgin in western Europe” and inspired numerous texts and artworks. I chose the topic of Marian devotion in López de Córdoba’s Memorias because I was intrigued by the significance of the Virgin Mary to women in medieval Spain, and while “a mother figure is a central object of worship in several religions,” Christianity as a whole is heavily entrenched with patriarchal themes, so it was interesting to research the role that a feminine religious figure had for women in medieval Spain, as demonstrated in the Memorias.

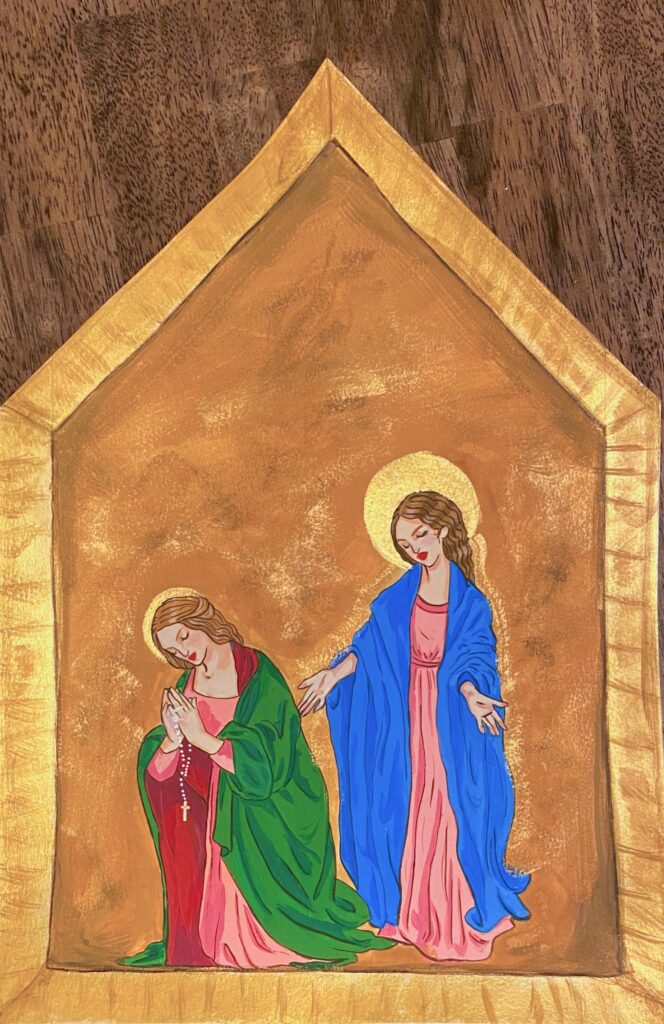

For my project, I chose the medium of gouache paints on watercolour paper, as this is a medium that I have prior experience with and am comfortable using, in addition to the opacity of the colours that this particular paint provides. Gouache paints act like a mix between watercolour and acrylic paints, as they are water activated and can be used similar to watercolour paints if desired, but can also come off as vibrant and opaque, making it a forgiving medium as it is easy to rework. While researching medieval art, one of the commonalities that I noticed was the use of vibrant primary and secondary colours, such as red, blue, green, and pink, particularly on the clothing of the figures, which prompted me to use this particular medium so that I could mimic the vibrancy of the colours in my own project and imitate the style and feel of medieval paintings which are so recognizable, such as in Lorenzo Monaco’s David. Additionally, many of the paintings I looked at either had very detailed backgrounds, or a plain background of black or gold; for my own project, I chose to imitate the simple gold background, as I didn’t want to distract from the central figures in the painting.

My painting consists of two central female figures: a woman praying on her knees, with a second woman standing closely behind her. These two figures represent Leonor López de Córdoba and the Virgin Mary, and reflect López de Córdoba’s descriptions within her Memorias. In the text, Leonor “actively prays to the Virgin for the restoration of her honor,” and she describes how “For thirty days [she] prayed to the Virgin St. Mary of Bethlehem,” and said “three hundred Ave Marias.” Prayer is an important aspect of the text, and also Leonor’s relationship to Mary and her faith as it demonstrates her devotion and piety, so I wanted to depict this in my artistic representation. The Virgin Mary stands behind the praying figure of López de Córdoba in a reassuring way, to represent the comfort that her faith in Mary brings and the involvement of the Virgin in the miracles that López de Córdoba discusses throughout her text, and the “tender representations” of Mary in medieval art that emphasize her maternal and feminine nature that is important to Leonor and other medieval women. Often, in medieval art, the Virgin Mary is depicted in blue, which I took into consideration when choosing a colour palette for my piece, as it makes the figure more recognizable as the Virgin Mary, in addition to the gold halo that signifies her status as an important religious figure. I also chose the shape of the painting after looking at several different devotional panels and shrines, to reflect the fact that Leonor “prays to two favoured images of the Virgin in Cordoba.”

While I only looked at one primary source for this research project, it was actually only after reading López de Córdoba’s Memorias that I decided to do an artistic representation rather than an essay, as the detailed descriptions of her devotion to the Virgin Mary and the solace she takes in her faith inspired me to create the painting that I did. I was intrigued by how she dedicates not only her text, but her entire life to the Virgin Mary, and believes that everything that she experiences, including the numerous hardships such as the plague outbreak she discusses, are “God’s will.” She even goes so far as to explicitly blame her own sin for several deaths, stating that “through my sins, thirteen persons who watched over [her adopted son] by night all died,” demonstrating her wholehearted devotion to and belief in her faith, and the impact that religion had on the lives of those in medieval Spain. My representation was also influenced by the emphasis placed on “the Rosary or chain of prayers in the second part [of the Memorias] to engage the reader in an implicit discussion of temporal injustice and divine mercy” as discussed by scholar Frank Dominguez. Amy Hollywood’s argument that “medieval women make use of the very gender subordination that constrains them as the condition for and source of agency, an agency ultimately ascribed not to religious women themselves, but to God,” was also influential to my project, as López de Córdoba’s writing can be taken not only as an autobiography, but an account of the miracles she has witnessed and an encouragement for others to also put their faith in God; the emphasis placed on the will of God and of the Virgin Mary throughout the primary source demonstrates this argument. The primary and secondary sources that I explored for this project were both fascinating and influential to my representation of Marian devotion and feminine religious identity in medieval Spain.

The artistic representation I did for this project is meant to reflect the devotion to and identification with the Virgin Mary as a feminine religious figure for Christian women in medieval Spain through my analysis of Leonor López de Córdoba’s autobiography, Memorias.

Bibliography

Bartolo, Andrea di. Madonna of Humility, The Blessing Christ, Two Angels, and a Donor. Ca. 1380-1390. Tempera on panel, 28.4 x 17 cm. National Gallery of Art. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.160.html.

Credi, Lorenzo di. The Virgin Adoring the Child. Ca. 1490-1500. Oil on wood, 86.4 x 60.3 cm. The National Gallery. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/lorenzo-di-credi-the-virgin-adoring-the-child.

Domínguez, Frank. “Chains Of Iron, Gold And Devotion: Images Of Earthly And Divine Justice In The Memorias Of Doña Leonor López De Córdoba.” In Medieval Iberia: Changing Societies and Cultures in Contact and Transition, edited by Ivy A. Corfis and Ray Harris-Northall, 30-44. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2007.

Flandes, Juan de. Saints Michael and Francis. Ca. 1505-1509. Oil on wood, gold ground, 89.9 x 83.2 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436802.

Giles, Ryan D. “No hay quien vele a Alonso: Imitatio Mariae and the problem of conversion in Leonor Lopez de Cordoba’s Memorias.” In Gender and Exemplarity in Medieval and Early Modern Spain, edited by Maria Morras, Rebecca Sanmartin Bastida, and Yonsoo Kim, 193-211. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

Hollywood, Amy. “Gender, Agency, and the Divine in Religious Historiography.” The Journal of Religion 84, no. 4 (2004): 514-528.

Kahil, Janet. “Recent Developments in the Academic Study of the Cult of the Virgin Mary.” The Journal of Religious History 33, no. 3 (2009): 337-388.

López de Córdoba, Leonor. “Memorias.” Translated by Kathleen Lacey. In Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources, edited by Olivia Remie Constable, 427-434. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Monaco, Lorenzo. David. Ca. 1408-10. Tempera on wood, gold ground, 56.8 x 43.2 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436912.

Pesellino, Franceso. Madonna and Child with Six Saints. Late 1440s. Tempera on wood, gold ground, 22.5 x 20.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437276.

San Leocadio, Paolo da. The Virgin and Child with Saints. Ca. 1495. Oil on oak, 43.5 x 23.3 cm. The National Gallery. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/paolo-da-san-leocadio-the-virgin-and-child-with-saints.

“The Cult of the Virgin Mary in the Middle Ages.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001. Accessed June 19, 2021. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/virg/hd_virg.htm.

Recent Comments