The poem The Ring of the Dove is a lament to love in medieval Al-Andalus written by a Muslim scholar named Ibn Hazm. Ibn Hazm was a writer of theology and law in Cordoba during the early11th century. He lived from 994 to 1064 A.D. and was renowned for his devotion to non-fictitious writings. This poetic story is his only well-known work of fiction (Constable and Damian: 2012:103).

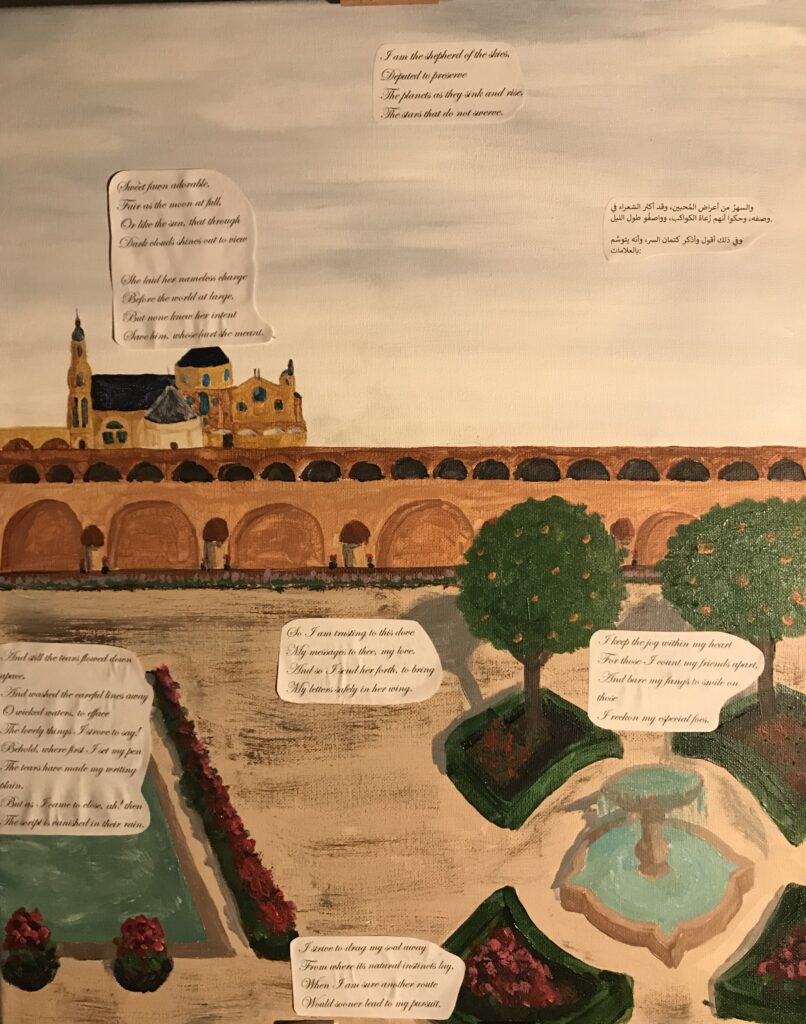

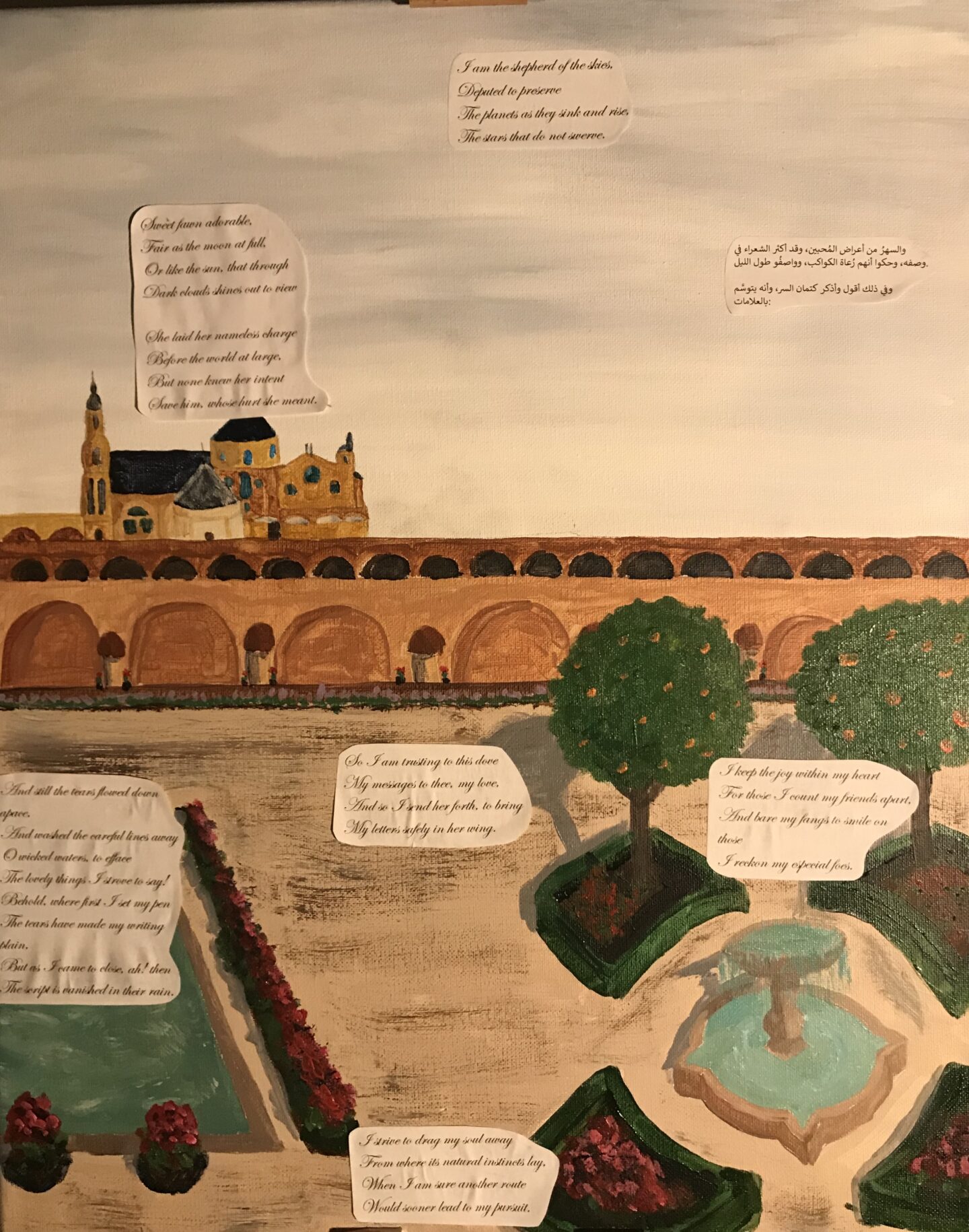

I chose to use the novel The Lions of Al-Rassan as inspiration for my artwork. I used acrylic paint and chalk pastel to recreate my imagining of the gardens of the palaces of Cartada and Silvenes in the fictional Al-Rassan. Because my project is based on the work of Ibn Hazm, his poem The Ring of the Dove, and the character Ammar ibn Khairan is based on Ibn Hazm, I found inspiration for my artwork in his character in the novel. The very first scene of the novel, when the reader is introduced to Ammar ibn Khairan, he is in the gardens of the palace of Al-Fontina in Silvenes to assassinate the last khalif of Al-Rassan. These gardens are described vividly, and the last garden, where Ammar kills the khalif, is a small garden called the Garden of Desire. It is described as “the most jewel-like of all,” and the khalif is sitting on a fountain clad in white. The imagery in this passage stuck with me, particularly the description of the palace gardens as being “built to break the heart.” Because the poem of the real-life poet, Ibn Hazm, is focused on love and lovers and heartbreak, I found this scene of the novel to be a very natural thought upon which to begin my artwork.

This poem has been studied widely as a means of seeing into the Al-Andalusian views on sex, love, marriage, slavery, race and gender. The idea of romantic love being compatible with sex slavery for Muslim men and non-Muslim women is evident in the first half of the poem (Fox Jr. 2019: 54). As well, this poem demonstrates how love, sex and marriage were viewed in historical Muslim societies, and can be used to understand the evolution of how current Muslim’s view love, sex and marriage. Dr Jean Dangler (Dangler 2015:335) notes that in modern times, marriage in Islamic societies is often not associated with love and sex the way it is seen to be in both The Ring of the Dove by Ibn Hazm and in Muslim poet Ahmad ibn Yusuf al-Tifashi’s erotic book from the 13th century, Nuzhat al-albab fima la yujad fi kitab. It is important to understand these views of medieval Muslims so that modern associations with Islamic marriage, love and sex, are not skewing the understanding of the poetry. Poetry was a key part of fiction writings in medieval Spain during the Al-Andalusian period. Other poets besides Ibn Hazm and al-Tifashi have shown not only romance and marriage, but the concept of Convivencia in Iberia during the time of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim cohabitation of Al-Andalus. Another poet, Ibrāhīm ibn Sahl, lived in Al-Andalus during the 13th century as well, and was a Jewish convert to Islam (Friedman 2018:335). His work falls within the same period and again shows how love, marriage, and daily life was different both from modern times and how the lives of each individual held different perspectives.

The stanzas from The Ring of the Dove featured in my art project vary in meaning and length. They were chosen either due to connections between the novel by Guy Gavriel Kay and the poem, or due to their importance to the overall mood and imagery I am attempting to portray through my artwork. For instance, the stanza taken from the chapter Of Breaking Off:

I keep the joy within my heart

For those I count my friends apart,

And bare my fangs to smile on those

I reckon my especial foes. (1)

This waas chosen and placed near the fountain because that is the lovation in the novel where the poet Ammar Ibn Khairan assassinates the last khalif, a man who felt Ammar was a close friend, only to be betrayed. I felt that a stanza on friendship and enemies was especially fitting.

The stanza taken from the chapter The Signs of Love:

I am the shepherd of the skies,

Deputed to preserve

The planets as they sink and rise,

The stars that do not swerve. (15)

This was chosen to be placed in the sky of my painting in hope of giving the viewer an insight into how the people who lived in palaces such as the one I painted might have thought about the sky. For this reason, I also included the original Arabic translation of the stanza to include as well:

والسهرُ من أعراض المُحبين، وقد أكثر الشعراء في وصفه، وحكوا أنهم رُعاة الكواكب، وواصفُو طول الليل. وفي ذلك أقول وأذكر كتمان السر، وأنه يتوسَّم بالعلامات:

The two stanzas from the section Of Illusion by Words:

Sweet fawn adorable,

Fair as the moon at full,

Or like the sun, that through

Dark clouds shines out to view (1)

She laid her nameless charge

Before the world at large,

But none knew her intent

Save him, whose hurt she meant. (6)

These stanzas were placed by the main part of the castle, outside of the garden, as I felt that it would have taken place indoors. I included it as it showed not just peace within love but also heartbreak, which is central to the theme of the poem, and something I hoped to capture in my artwork. The scene from which they were taken begins with the first stanza describing a woman who was in love with a man, and after a time he made an improper suggestion of a sexual nature, so she sang a song that is described in the final stanza (6) as a “nameless charge” to her ex-love.

Another stanza from the chapter Of Breaking Off:

I strive to drag my soul away

From where its natural instincts lay,

When I am sure another route

Would sooner lead to my pursuit. (7)

This stanza was chosen, similarly to the previous, to demonstrate the heartbreak of the writer.

The stanza taken from the chapter Of Correspondence:

And still the tears flowed down apace,

And washed the careful lines away

O wicked waters, to efface

The lovely things I strove to say!

Behold, where first I set my pen

The tears have made my writing plain,

But as I came to close, ah! then

The script is vanished in their rain. (6)

This stanza was chosen to precede the final stanza. It shows the writer’s pain in writing a love letter. I placed it near the pool as I felt the water would be able to show the vast amount of tears that the writer describes.

The final stanza, taken from the chapter Of the Messenger:

So I am trusting to this dove

My messages to thee, my love,

And so I send her forth, to bring

My letters safely in her wing. (4)

Shows the writer finally sending the letter he wrote to his love, after so many tears were shed in writing it.

Overall, this project was meant to mix the visual aspects of poetry with visual art. In using what I learned about Convivencia and the controversy of whether or not it truly existed, I created a piece of artwork that reflected an interfaith love story filled with difficulty and heartbreak.

References Cited

Constable, Olivia Remie, and Damian Zurro, eds.

2012 Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim, and Jewish

Sources. University of Pennsylvania Press. Chapter 18: p103-106

Friedman, Rachel Anne.

2018 Scriptural Intertextuality in the Poetry of a Late Andalusi

Convert. Prooftexts 36, no. 3: 335-354.

Ibn Hazm.

994-1064 Ṭawq al-ḥamāma (The Ring of the Dove). Accessed from: Luzac & Company, Ltd. 46 Great Russell Street, London. Translated by: A.J. Arberry, Litt.D., F.B.A

Dangler, Jean.

2015 Expanding Our Scope: Nonmodern Love and Sex in Ibn Ḥazm al-Andalusī’s Ṭawq al-ḥamāma and Aḥmad ibn Yūsuf al-Tīfāshī’s Nuzhat al-albāb fīmā lā yūjad fī kitāb. Africa Today, 61(4), 12-25.Friedman, Rachel Anne. Scriptural Intertextuality in the Poetry of a Late Andalusi Convert. Prooftexts 36, no. 3 (2018): 335-354

Kay, Guy Gavriel.

1995 The Lions of Al-Rassan. Toronto: Viking.

Fox Jr, Kevin. A.

2019 The Ring of the Dove: Race, Sex, and Slavery in al-Andalus and the Poetry of Ibn Hazm. Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies 42(3): 54-68.

References Cited Constable, Olivia Remie, and Damian Zurro, eds. 2012 Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources. University of Pennsylvania Press. Chapter 18: p103-106 Friedman, Rachel Anne. 2018 Scriptural Intertextuality in the Poetry of a Late Andalusi Convert. Prooftexts 36, no. 3: 335-354. Ibn Hazm. 994-1064 Ṭawq al-ḥamāma (The Ring of the Dove). Accessed from: Luzac & Company, Ltd. 46 Great Russell Street, London. Translated by: A.J. Arberry, Litt.D., F.B.A Dangler, Jean. 2015 Expanding Our Scope: Nonmodern Love and Sex in Ibn Ḥazm al-Andalusī's Ṭawq al-ḥamāma and Aḥmad ibn Yūsuf al-Tīfāshī's Nuzhat al-albāb fīmā lā yūjad fī kitāb. Africa Today, 61(4), 12-25.Friedman, Rachel Anne. Scriptural Intertextuality in the Poetry of a Late Andalusi Convert. Prooftexts 36, no. 3 (2018): 335-354 Kay, Guy Gavriel. 1995 The Lions of Al-Rassan. Toronto: Viking. Fox Jr, Kevin. A. 2019 The Ring of the Dove: Race, Sex, and Slavery in al-Andalus and the Poetry of Ibn Hazm. Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies 42(3): 54-68.

Recent Comments